“When’s the white college World Series?”

“Are these not the people who wanted desegregation in the first place?”

“Totally reverse racism…”

These comments and more were made following a story on a Jacksonville news station website after Edward Waters won the Tyson Foods Black College World Series. As the head baseball coach at an HBCU, I experienced a variety of emotions reading those comments. I felt anger, frustration and resentment, but also recognition. I had relatively few black teammates as a baseball player growing up in Lexington, Kentucky and as an undergraduate player at Kentucky Wesleyan College. We had a journalism major one year at KWC who proposed writing an article claiming our coach was racist because we had only one black player during the previous three seasons. When the journalism student asked my opinion about it, my 20-year-old self answered it simply as black athletes preferred playing basketball or football. I assured him our coach wasn’t racist, he just didn’t have many talented black players in the area to recruit.

For some reason at that age, I didn’t think that much about the reasons behind why black athletes weren’t playing baseball. I grew up watching and imitating players like Rickey Henderson snapping his glove at fly balls, Willie Stargell windmilling hit bat at home plate in his stance and Dave Stewart staring down hitters from the mound. Baseball in the 1970’s and 1980’s had players who had grown up watching Jackie Robinson or hearing their parents tell stories of his exploits. Even though these role models were readily available, I only had one black teammate in high school and two black teammates for three years on my summer travel baseball team. I didn’t yet understand the larger forces which were limiting baseball opportunities for many black athletes.

Actions often have intended and unintended consequences. Branch Rickey’s push to integrate Major League Baseball helped open doors for men like Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby, Satchel Paige, Roy Campanella and countless other black baseball players throughout professional baseball. It’s a story we’re all familiar with, but what many of us didn’t know, and I wasn’t familiar with until recently, was how it hastened the demise of the Negro Leagues. Major League Baseball began signing the top Negro League stars without compensating their teams, and as the minor leagues desegregated, Negro League teams folded as more of their best players pursued minor league opportunities. In the luster of books and movies detailing the story of Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey, the demise of teams like the Kansas City Monarchs, Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays was largely forgotten.

Black participation in professional baseball peaked in the 1960’s and 1970’s and began to gradually decline throughout the 1980’s from its high of nearly 20% black MLB participation in 1981. Major League Baseball sought to address this decline at the behest of John Young, a Baltimore Orioles scout. Young founded the Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities (RBI) program in Los Angeles in 1989, and it has expanded throughout the United States and other countries. The RBI program has impacted thousands of young baseball and softball players since its humble beginnings in South Central Los Angeles and remains actively supported by Major League Baseball through the construction of first-class facilities and equipment.

I attended the Southfield Showcase this week in Detroit with four teams from Detroit and four teams from Chicago. Nearly 200 players participated in a showcase and series of games in order to be evaluated by college coaches from the midwest and southeast. The Detroit and Chicago RBI programs, and other programs in each city, are putting together high-level instruction and competitive playing opportunities for some players who might not normally receive them. These programs are impacting young men (and women in the softball organizations) and exposing them to widespread collegiate playing and educational opportunities.

However, the MLB/RBI investment has still not paid off in a substantial increase in black players in college or professional baseball. The percentage of black professional baseball players is under 10%, and according to the 2020 NCAA demographics database, black players made up approximately 5% of NCAA baseball players. Anecdotally speaking, I’ve seen the number of black players in college baseball remain stagnant during my nearly 30-year coaching career. Why hasn’t the movement to get more black players in college and professional baseball made a substantial difference? Where is the disconnect? More importantly, does it matter, and why?

Receiving an athletic scholarship or the opportunity to play professional sports is a near unparalleled accomplishment and goal for amateur athletes. It represents the culmination of years of hard work and an acknowledgement of one’s athletic abilities. It’s also a way out for many people of lower socioeconomic means. Baseball has always been a sport of accessibility for anyone who wanted to play until recently. In the last 30 years, the rise of travel baseball, private hitting and pitching lessons, and a lack of adequate facilities and equipment has turned away many promising young athletes from baseball.

This rise in expense has combined with the unintended consequence of Title IX when it comes to athletic scholarship opportunities for male athletes. In order to help universities comply with Title IX’s provision calling for “substantially proportionate” athletic opportunities, the NCAA has limited Division I institutions to 11.7 baseball scholarships and Division II institutions to 9 scholarships. Most collegiate baseball rosters range from 25-35 players (with a maximum of 27 receiving baseball scholarship money in Division I), which means very few baseball players receive a full ride without some combination of athletic, academic and financial aid. Since the 1980’s young black athletes of lower socio-economic backgrounds have more commonly embraced basketball and football as a more promising means to financial success and mobility.

Now the question is, “why does this matter?” This is a question I have wrestled with at various times of my playing and coaching career. Isn’t this just an acceptable part of our changing society? Is it that important that black athletes aren’t playing baseball in the same numbers as basketball and football? This isn’t a question anyone else could answer for me, it’s an answer I had to come up with myself. To me, baseball is a game that is worth being experienced by anyone who wants the opportunity. Baseball is too good of a game to deny anyone because they can’t afford to play. This is more than a black and white problem; this is an issue of inclusion. Nobody is asking for a handout or a guarantee, simply removing barriers that prevent athletes without the financial means to participate in baseball at a high level.

Several solutions have been discussed by various groups throughout amateur and professional baseball. The RBI program, The Players Alliance, Minority Baseball Prospects, Black College Nines, and the American Baseball Coaches Association Diversity in Baseball Committee are some of the more well-known groups working on increasing the participation of black players in all levels of baseball. Some of the more widely discussed solutions include investing in youth facilities and equipment, increasing NCAA baseball scholarship limits, improve recruiting opportunities for black baseball players, and increasing the visibility of Historically Black College and University (HBCU) programs.

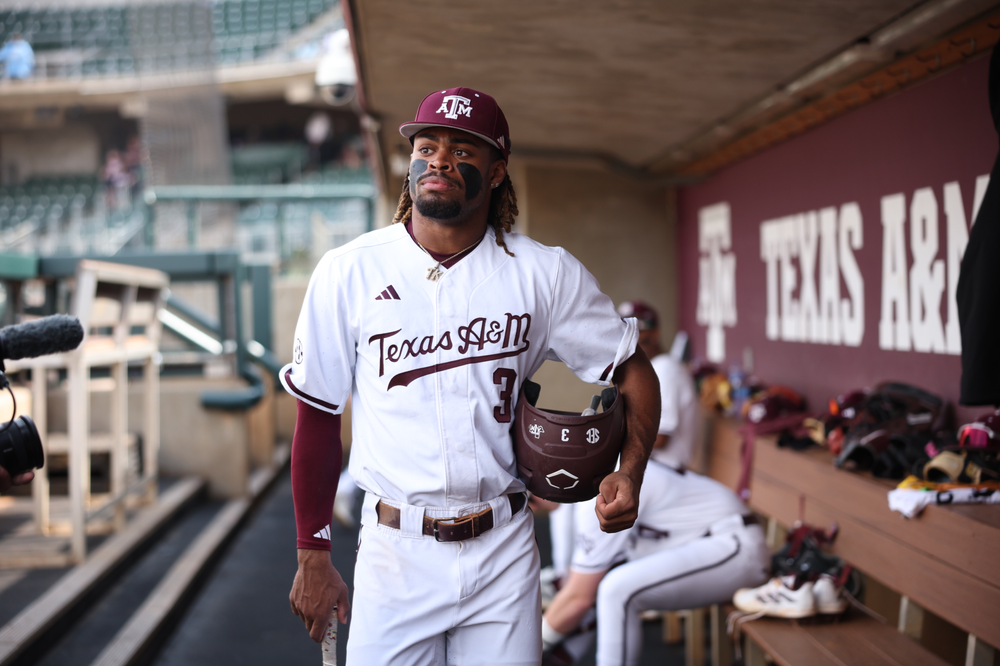

The 2022 Tyson Foods Black College World Series was a step in the right direction for the final above-mentioned goal. Much like the National Christian College Athletic Association World Series is made up of Christian schools and universities, this tournament is made up of HBCU programs. The tournament is not limited to black players or coaches, just to schools with the HBCU designation. It gives our players an additional goal to strive for during the season and helps highlight the programs fortunate enough to participate. Our experience in winning the Division II bracket of the World Series has drawn substantial positive attention to our program and are the types of experiences that can help inspire young athletes.

When I look back at the questions posted at the beginning of this article, I’m reminded there are people who don’t understand the purpose of what we are doing and others who look down on what we are doing. Several people tried to convince me to reconsider when I was offered the head coaching job at Kentucky State University ten years ago. One well-known high school coach in the area told me, “Go to that jungle school for a few years and improve the team and move on to somewhere better.” Others looked at the program’s streak of losing seasons since 1988 and said it was a lost cause. I can’t say that I have loved every moment of the challenge, but I’m proud of the progress we’ve made in these last ten years.

Baseball is a great game that was always meant to include everyone, and while watching teams competing at the Southfield Showcase this week, the answer to my question about why it’s commendable to increase black participation in baseball was confirmed. I loved playing baseball growing up and I love coaching it now. It’s helped form many of my closest friendships, taught me important life lessons, and even brought me and my wife together. It had taken a long time for HBCU programs like ours at Kentucky State University to fall behind competitively, and it’s taking time to improve. We’re starting to see the results of coordinated efforts of individuals, organizations and corporate sponsors in increasing participation and the experience of playing at HBCU programs. Baseball may not be for everyone, but everyone who wants to play baseball should receive the opportunity to rise or fall based on their own merits. The 2022 Tyson Foods Black College World Series is one small but important step among many in realizing this vision.

Robert Henry has been at the helm of the Kentucky State baseball program since the 2013 season. Henry earned his Bachelor’s in History and Secondary Education (minors in English and Physical Education) from Kentucky Wesleyan College and a Master’s in General History (emphasis in United Sates History) from Western Kentucky University. A member of the American Baseball Coaches Association since 1998, Coach Henry has published articles in Collegiate Baseball Newspaper and Coaching Digest and has served as a professional scout for the Kansas City Royals.