The path of the Great Migration led many people from tucked-away rural parts of the Deep South, like Mississippi, to muscular, bustling northern cities, like Chicago. Marvin Freeman, born on the South Side of Chicago in 1963, traveled against that grain to make his name.

The path of the Great Migration led many people from tucked-away rural parts of the Deep South, like Mississippi, to muscular, bustling northern cities, like Chicago. Marvin Freeman, born on the South Side of Chicago in 1963, traveled against that grain to make his name.

As a talented pitcher for Chicago Vocational High School in the Public League, Mr. Freeman quickly earned recognition throughout the city and caught the attention of Major League Baseball scouts. The Montreal Expos drafted him following his senior year in high school, but Mr. Freeman’s goal was to attend Jackson State University. He lived out that dream, learning valuable lessons, expanding his education and growing into a man.

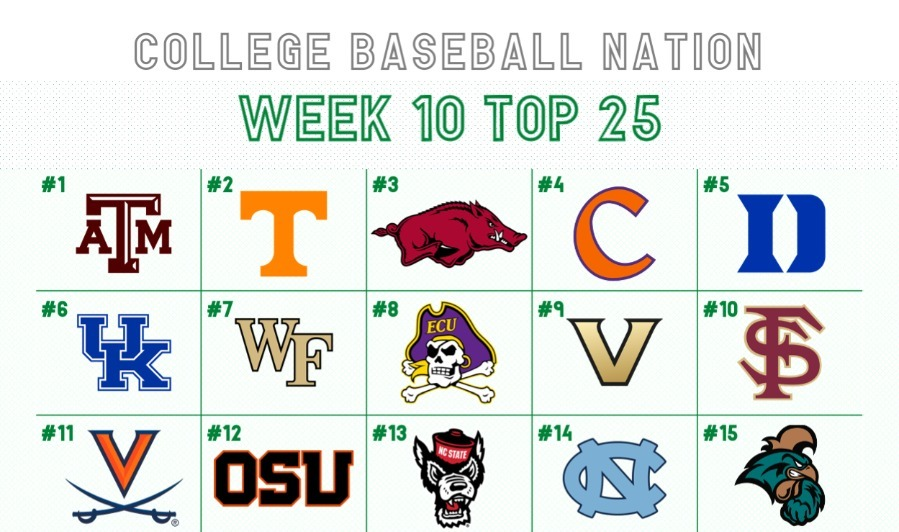

Mr. Freeman was part of an era of Tigers baseball from the late 1970s through the 1980s under legendary Coach Robert Braddy that saw five alumni become significant contributors in Major League Baseball: Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd, Dave Clark, Wes Chamberlain, Curt Ford and himself. He played on the first HBCU ballclub that qualified for the NCAA Regionals, the 1982 Tigers squad that earned the Southwestern Athletic Conference’s (SWAC) first automatic bid into the postseason.

After his junior year at Jackson State in 1984, he was a second-round draft pick of the Philadelphia Phillies and quickly ascended their minor league system, making his MLB debut in September 1986. He pitched from 1986 to 1996 with the Phillies, Braves, Rockies and White Sox. Currently, Mr. Freeman serves as a roving pitching coach and offers tips, training and insight through his various social media channels. He also remains active with the Marvin Freeman Youth Foundation, which raises money to defray the costs of travel baseball for young players whose families need assistance.

“My wife, Arnetta, has always been pushing me to be more than I think I am. She’s probably the reason I made it to the major leagues. We went to high school together, and we talked about this thing when we were 15 years old,” Mr. Freeman told Black College Nines. “We’ve been married 38 years. Both kids graduated from college. It’s been a fairytale life I’ve been able to live, and I owe it all to God for blessing us with these opportunities.”

The following is a lightly edited version Mr. Freeman’s conversation with Black College Nines writer Douglas Malan on April 27, 2020.

I know you were really young growing up in Chicago in the ‘60s during the riots. But do you remember any of that?

I was born in ’63, so when the riots were going on, I was 6 or 7 years old. We were shielded from a lot of that stuff. Our parents (father Sonny and mother Bobbie) didn’t really let us run with the neighborhood kids the way everyone else did. We were more sheltered than was usual for our neighborhood, but it turned out to be a good thing. Some of the guys I grew up with, they didn’t fare too well because they had a lot of freedom when they were young.

Even when I got old enough to start hanging out with guys in college and old enough to go to parties, I would always leave. It gets to a point around 11 o’clock when everything starts jumping off and I was like, hey man, I gotta go. I could almost recognize when those troubled time periods came about. I owe that to my parents making me realize what was going on in my surroundings and being a bit more aware of how things get started. It was a good basis for me to start my own way of policing myself.

What did you like to do when you were a kid?

We used to play this game called Strike Out where you’d throw a rubber ball against the wall (into a drawn box). You didn’t really need anyone else. I was always practicing my pitching and people in my neighborhood thought I was a little crazy. I wouldn’t even have a batter up there. I loved baseball so much by growing up and watching the Cubs and the White Sox on TV, and I’ve always wanted to be a baseball player. I always imitated Fergie Jenkins and Lee Smith on the mound. I’d rush home after school and watch those last three innings of the Cubs games.

I tell kids my travel ball was throwing against that wall for hours at a time. I guess it was grooming my own habits in a way that I didn’t know how much the repetition would pay off later on.

How did you end up at Vocational High School?

The high school that was in my neighborhood was really not that academically challenging. My parents had us go to a vocational school where we had to get on the bus and you had to actually test to get in. It was more challenging academically, so you had to have more focus.

The high school that was in my neighborhood was really not that academically challenging. My parents had us go to a vocational school where we had to get on the bus and you had to actually test to get in. It was more challenging academically, so you had to have more focus.

Back then, we had businesses in America where people could actually get jobs, where you could go and establish a career in the local factories and make a pretty good living for your family with benefits. The vocational school trains you in certain areas. I was always pretty good with my hands, so I was in carpentry and woodworking, or cabinetmaking as they called it. I was a pretty good cabinetmaker and I entered an industrial arts fair when I was a junior in high school. The project I made was a mahogany roll-top desk and it took the whole year to make it. I entered it in the fair and won second place with it.

I heard you spent time making violin bows, too.

The guy who owned the bow shop, John Norwood Lee in Chicago, he’s still in business making concert-quality violin bows for all the symphonies around the United States. He saw some of the work that I did and was interested in training a young high school student in bow-making and wanted to make sure the student had some woodworking skills. So he talked to my shop teacher and my shop teacher recommended me for the position. And that’s how that bow-making gig came along. I was making $27 an hour as a senior in high school.

Whew, that is a good gig!

I know, man, I know. It almost kept me off the mound. (laughing) I was like, shoot, I’m making $600/$700 a week and I’m working part-time. I could make a living doing this. My man John had a little bit more foresight. He knew being drafted out of high school (by the Montreal Expos) was rare, and he encouraged me to see it through and see how far I could go with the baseball career.

He probably figured the bows would always be there waiting if you needed to come back.

Absolutely, and as a matter of fact, that’s what I used to do in the offseason. I would go back and work in the bow shop, restringing and rehairing violin bows, maybe repairing some of the cheaper ones. We had bows come in that were 75 to 100 years old being restored. And I ended up breaking a $75,000 Tourte bow. It was like the Stradivarius of violin bows. I was so good at my craft, he trusted me working on that. And then when I broke it, I thought oh boy, I’m getting ready to get fired. Luckily, it was over-insured and they ended up making a slight profit. So I asked, “Hey man, you want me to break up some more of these bows? I can do that.” (laughing)

We’re still pretty close to this day. He donates to my foundation to serve kids who aren’t as fortunate enough to afford the expenses it takes for offseason training and travel ball. Our foundation has been able to bridge the gap for a few kids and allow them to display their talents without all the financial burden.

Did you have time or interest in playing other sports in high school?

I grew up playing basketball, because basketball is king in Chicago. I’m playing against Terry Cummings and Mark Aguirre in high school and they’re just ripping me a new one every time out. I’m giving up 30 points, 40 points and I’m supposed to be the defensive specialist. I’m like, hey, I’m gonna have to rethink this basketball thing.

Basketball season had just ended and me and a buddy of mine were walking past where they were having baseball tryouts. I had never played on a Little League team. I went to the baseball tryouts as a tenth grader and said, “Coach, I can pitch.” He says, “OK, lemme see what you got.”

Now the equipment in the Public League, it wasn’t pro type, it wasn’t grade A, it wasn’t top of the line. This is the reason why I tore the pocket off the catcher’s mitt, not because I had exceptional stuff. As I get older, the story evolves into I was so nasty that’s why I was tearing up catcher’s gear. (laughing)

I end up making the team and the first game that I pitched was against my old neighborhood buddies that I played sandlot ball with growing up in the park. It was so comfortable facing them because I knew they couldn’t hit me. I threw a no-hitter, and I took off from there.

I gave up basketball after that because I knew a 6-4 basketball player is not the same as a 6-4 pitcher.

How did Jackson State become part of your plan?

I really wanted to focus on getting in a situation where I could get a college scholarship. We had a guy at our school that ended up going to Jackson State named Charlie Scott. He played pro ball for the Montreal Expos. When he went to Jackson State, that was all that people were talking about in high school. I was a sophomore in high school and that’s what I set my goal for.

I didn’t even know Jackson State was in Mississippi, but that’s where I was going.

As my high school career was getting more and more developed, I was getting more and more offers from different colleges. Big 10 schools, Big 8. Nebraska really wanted me. But my high school coach was a guy that really didn’t do a lot to help or even advocate guys going to college. When we graduated, we found 50 or 60 college letters in his desk drawer that he never even gave us. I didn’t see anything until about a week before graduation. It was too late to actually register and get accepted to college.

I thought I’d just stay home, go to one of the local colleges and continue to work at the bow shop. And then Coach Braddy, he had relatives in Chicago, and he had heard about me through some other high school coach. He came to my house with his brother in June. When he said, “Jackson State,” my ears went up. It was like I predicted this almost two years earlier.

College was gonna start in another six weeks, right? I had a 23 on the ACT, so grades were never a problem. And I got drafted in the ninth round by the Expos out of high school. But the Expos’ offer was such an insult. I was like, man, I’m making more money than this at the bow shop. Why would I want to leave home and play baseball for less money and I don’t even know where I’ll end up?

I declined to go play pro ball. I knew I wasn’t mature enough to go off as an 18-year-old and have a pro career when I haven’t even left home yet. I don’t think I’d been out of the city other than to see relatives on vacation with the family. Now you’re expecting me to be a grown man and play in a sport that’s a job now? I knew I wasn’t ready for that.

So Coach Braddy says, “I hear you have a pretty good fastball. I’ve got my brother here. You’ve got a park about two blocks away. I want you to go over there and throw to him.” And I’m like, “This old dude gonna catch me?” (laughing) And his brother kinda took offense, like, yeah, I can catch you, man!

We warmed up a little bit and I got up on the mound. The first pitch I threw, I’m tellin’ you, I was bringin’ cheese. He held his glove up, and it went right past his glove, right past his ear, right past his head. I only threw one pitch off the mound, and he was like, “Uh, nope, I’m not catchin’ this.” And Coach Braddy said, “Yeah, we want you, man.”

That’s how I got to Jackson State. And when I got inducted into the Jackson State Hall of Fame and I’m doing my speech, I said, “I chose Jackson State over a pro career and I turned down HUNDREDS of dollars to sign here.”

That’s how I got to Jackson State. And when I got inducted into the Jackson State Hall of Fame and I’m doing my speech, I said, “I chose Jackson State over a pro career and I turned down HUNDREDS of dollars to sign here.”

I was in a bubble on the South Side of Chicago. That’s what I knew. I was glad I was able to get out and expand my horizons and learn there’s a lot more in the world than just the South Side.

What was it like being at Jackson State?

Back then, we used to take the Amtrak. There were probably about 30 kids on the train going from Chicago down to Jackson State. It was like a party train. And I was like, college is gonna be GREAT! I’m gonna get out here and it’s gonna be…WOO! And then I got off that train, and we got on that campus, and Jackson State was not what I thought it was gonna be. (laughing)

The dorm was like a prison barracks, brick walls. You couldn’t control the air conditioner, so we had to put a cardboard box over the vent to control the air and the heat. And when I got a chance to tour the baseball field, I’m walking around and I asked coach, “This is the practice field, right?” And he was like, “Nah, man. We cut the grass and we get those weeds down from along the fence, but this is where the magic is gonna happen.” It wasn’t the most pristine baseball field. But knowing I was getting a chance to play as a freshman, to be in the rotation and earn an opportunity to pitch, that’s what drove me to Jackson State.

I knew from talking to other guys who played for Coach, he was a standup guy. Even to this day, I love that man like he’s a second father to me and I see him as much as possible.

A lot of talented guys landed at Jackson State around that time – Oil Can Boyd, All-American and first-round draft pick Dave Clark, Wes Chamberlain…

You don’t see that anymore. You don’t see four guys getting drafted out of HBCUs, let alone four getting to the major leagues that all played during the same time period. Those are the days I long for and try and bring back. I even introduced my son (Justin) to HBCUs. He graduated from Southern two years ago and they won a (SWAC) championship ring.

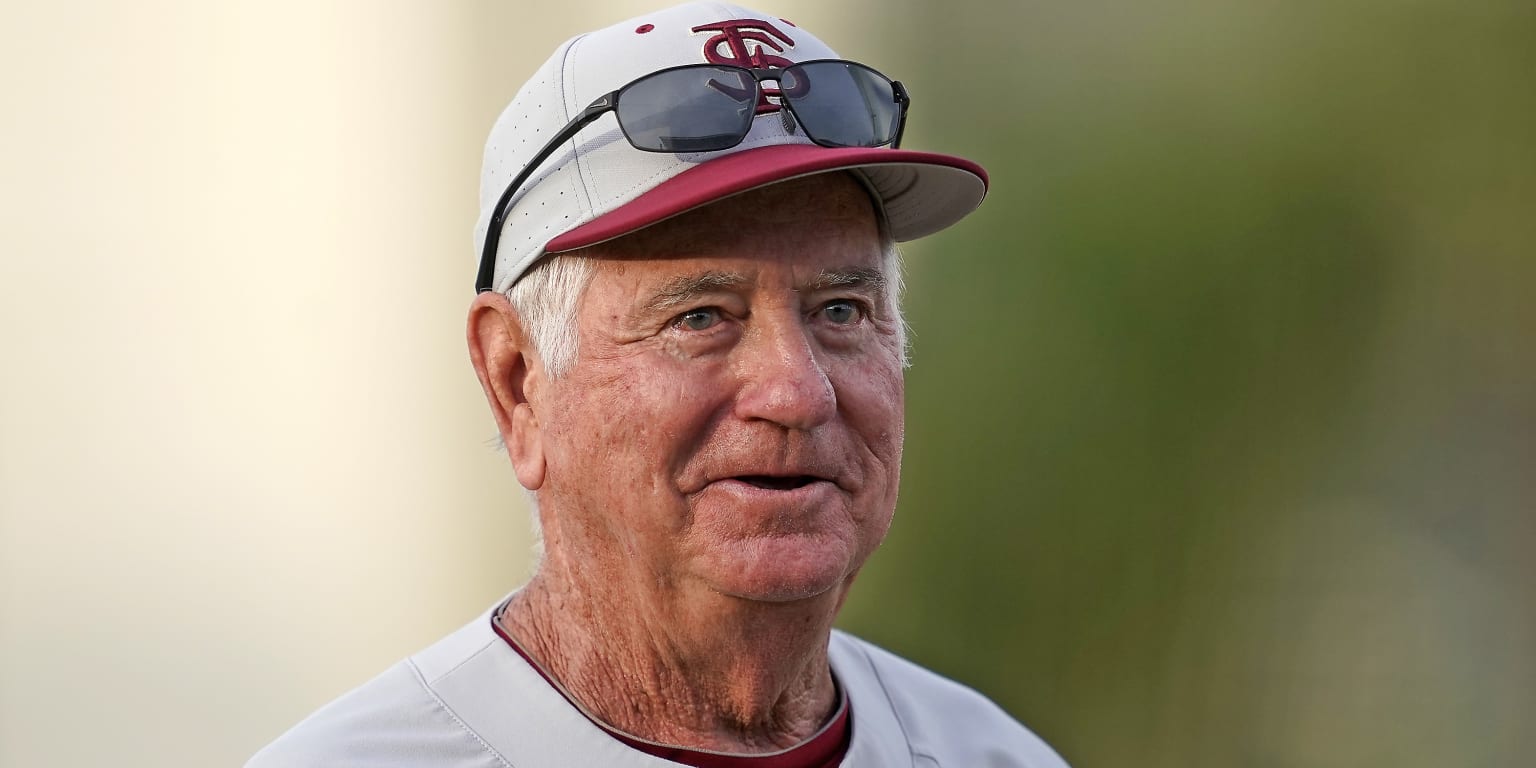

What kind of program did Coach Braddy run?

His specialty was hitting and defense. And he brought in Scipio Spinks. Scipio Spinks was a major league pitcher that grew up in Chicago and threw like 100 miles per hour in the ‘70s. The mentality he brought to us as a pitching staff is the same mentality I try to teach young pitchers today. You gotta be tougher mentally and you gotta be just as tough physically to make yourself a major league player.

Scipio would have us running. When we got to practice, we had to warm up with a seven-minute mile. And you’re talking about Jackson, Mississippi. It was 95 degrees. If you didn’t run it under seven minutes, you had to run it again after practice, on top of the other running we had to do as a team, which was 20 foul pole to foul pole and then 20 sprints from the left field line to the left center field gap. The running part, it was grueling. Sometimes we had to run and the dining hall was closing in 10 minutes, and if you didn’t get your running in, you didn’t eat. I was like, ‘God, please, let me make it through these three years so I can get up outta here.’

We took pitchers’ fielding practice, and we didn’t take it like when a coach stood at home plate and hit balls out to the mound. Coach Scips stood on the mound and put us on the back fence and would just hit absolute missiles at us. And we had to either get hit or catch the ball. I got a couple of videos that I put on my Instagram of me catching line drives hit right back at my forehead (from MLB days) and people were going, “Man, you had cat-like reflexes.” They didn’t understand that was something I actually worked on. It was not an accident.

I talked to Scipio a couple of days ago. He lives in Houston. I still keep in touch with the guys that had big effects on my life and made me become the coach that I am. I still draw from some of the same experience they used on me. It’s made me a better coach. It’s made me a better communicator.

As a freshman in ’82, you were part of the first HBCU to compete in the NCAA Regionals, the first year the SWAC champ got an automatic bid. What was that like?

We played down in New Orleans against the University of New Orleans and we played against Wichita State. Wichita State went on to the College World Series, and they had a really good team. We got a chance to see where we fell short at, and it was the depth. Once you get past those second or third starters and you got guys out there that don’t really have the…I’m gonna say it in a cruel way…don’t really have the balls to be out there, you find out who you can go to war with.

I imagine being an HBCU club, your experiences on the road in non-conference play weren’t always positive.

I have several life-growing experiences playing down in the Deep South where we’d go into other places to play – Alabama, Mississippi – and we’re playing teams that would not come to our park because they knew we were a different ballclub at our park. When we go to their park, it’s like, we’re gonna give you guys about three innings to enjoy a real baseball game and then it’s gonna turn to where it almost seemed like some of these guys’ uncles and dads were the umpires.

They even did a story about us on (ESPN’s) 30 for 30, about Mississippi State (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1f7c_VEJvIM) when they had Will Clark, Rafael Palmeiro, Jeff Brantley and Bobby Thigpen. They hit seven or eight home runs off of us (in 1984). They were talking about this game that they had played against Jackson State. Well, I pitched the first five innings of that game, and I was pitching five innings of shutout ball. And then I went out in the sixth inning and the same pitches weren’t strikes anymore. You got Will Clark and Rafael Palmeiro playing with an aluminum bat, and they know you’re not gonna get a breaking ball for a strike, you’re throwing BP. That was one of the most difficult games I had to deal with mentally because I had never experienced that level of biased umpiring in a game.

It built character in me. And when I got to face those guys in the pros with umpires actually calling those pitches for strikes, after the game they’d say, “Man, I didn’t know you had that pitch.” And I say, “I had it, but they weren’t gonna call it. So why would you think I got it if you ain’t gotta look for it?”

It leveled off when we got to the pros. But what can you do? You can’t control what the umpires do. You can’t control what’s being said in the stands. I mean, they were throwing chicken bones and watermelon rinds at us down there in Starkville. And I’m like, ‘What is going on with THIS?’ A kid from Chicago seeing that, it was real eye-opening.

I’d always heard about it but never really experienced it. That was one of the tough things that I had to get over when I went from Chicago down to Mississippi and how the baseball on the field changed.

You just hope nobody gets hurt. It’s a situation where you come out of it in one piece, you learn from it. It’s a teaching moment. It’s embedded in the fiber of America, so it ain’t gonna go away on the baseball field.

Were you a guy ready for intense on-field battles when you set foot on campus or did you have to learn a different level of toughness when you got to college?

I definitely had to learn it. As a high school pitcher in Chicago, the games were played in 40-degree temperatures and so most of the hitters were afraid to make contact. I’d never been hit. I’d never had to deal with somebody beating my brains out.

When I got to college, I pitched a game and I didn’t last two innings, and that’s never happened to me. I’m on the bus, tearing my uniform off, saying I’m transferring and I’m ready to go home, this ain’t supposed to be like this. And Coach Braddy was like, ‘Hey, man, look. The history of baseball says you don’t win ‘em all. What you need to do is find out why you were getting hit and work your butt off on not making those mistakes and be mentally tougher so that when you do get in a tough situation, it’s not panic mode.’ It was something all young pitchers are gonna have to learn.

You read your own press clippings and you start getting this inflated sense of your ego. That helps as well. If you think you’re good, either you’re gonna try and get better and work harder at it, or you’re gonna quit. And the ones that quit, they still regret it to this day when they think about what they should’ve done, talk about how they should’ve kept doing this or doing that. I have no regrets because I always tried the best that I could and I always gave it 100 percent every time out to try and see if I can get better, learn from those that were being successful, steal some of the things that they were doing and try to make it mine, find out why I was struggling when a guy who had lesser stuff than me was being successful. It came down to this guy is always ahead in the count, I’m always behind. This guy is throwing his breaking ball for strikes, I can’t get mine over.

I just knew that I had good stuff. I was a good competitor. I always felt that I could win, but even with that, you still have to execute. Once I started executing, that’s when I started taking off.

In 1983, you spent the summer playing in the Cape Cod League. What was that like measuring yourself against these top players in the country and what was it like being a Black ballplayer from a school those guys probably never heard of?

The year started off, I was going to the Jayhawk League and playing in Hutchinson, Kansas. And in Kansas, you know it’s 125 degrees, wind blowing. We were playing one day and you could see a tornado go across the outfield. It was deep but they were like, ‘we’re still playing.” And I said, “Dude, that’s a tornado right there.” And they say, “Oh, it’s going across, it ain’t coming this way. We’re good.”

The year started off, I was going to the Jayhawk League and playing in Hutchinson, Kansas. And in Kansas, you know it’s 125 degrees, wind blowing. We were playing one day and you could see a tornado go across the outfield. It was deep but they were like, ‘we’re still playing.” And I said, “Dude, that’s a tornado right there.” And they say, “Oh, it’s going across, it ain’t coming this way. We’re good.”

I played in Hutchinson, Kansas, for about three weeks. And in those summer leagues, you stay with a host family and they find you a job. The job that they found me, I was working at this place called the Unit Step Company. We made concrete porches and stairs. We’re pouring concrete. I’m doing manual labor. It was killing me. I’m saying, “Dude, I gotta pitch tonight.” I gotta take those blocks they use in the parking lot, and I had to put down fifty of those and nail them down with the spikes in it. When I got to the park, I’m just dogged. And everybody else is looking fresh and I ask these guys what jobs they were doing. Most of the guys said they worked at the ballpark, “landscaping.” Not cutting grass, but if they saw a dandelion, they’d go pluck it, and they’d hit all day. And I said, “Wait a minute. I didn’t come out here to be getting abused.”

I called Coach Braddy and he said he saw what’s going on, and he heard from some guys in Cape Cod who needed a pitcher. I said, “Before I go out there, make sure I have a job that I can be able to pitch that night without having to expend all my energy.” So when I got out to Cape Cod, I worked at this hotel resort where I drove a golf cart around with a walkie talkie, and if someone needed a towel or something, they’d put it on the cart for me. It was so easy, man. I had a chance to get in the right frame of mind for the game. I wasn’t exhausted.

When I got out to Cape Cod, I was the only Black pitcher in the whole league. All these guys were from Stanford, big colleges and universities all over the country, and they were ranked by Baseball America. Cory Snyder was out there. They called him Crash Man. He was crushing home runs out there and all this stuff.

I got out there and as soon as I got off the plane, I pitched two innings of relief. The two innings that I pitched, I ended up striking out five.

Three days later, I got a start. The first start I had, I went nine innings and struck out fifteen. And you know at the Cape, there’s scouts everywhere. I ended up pitching five games and I went 4-1. The only game I lost was a 2-1 game. Cory Snyder hit a home run off me in the ninth inning to win it. I could’ve easily been 5-0. I had a 1.98 ERA. And when I came back to Jackson State, I was like King Leonidas. I went out there and came back a king, All-American, my name was on the board.

Cape Cod set the tone because it gave everybody an opportunity to see how I could compete against guys that were supposed to be the best in college baseball. And I went out there and dominated.

It’s a thing I look back with fond memories of because I did really well when I had to. That’s what it’s all about. When you get an opportunity, you gotta cash in on it. You don’t know when you’re gonna get a second one. Especially for me being the only Black pitcher out there, from Jackson State, where guys were like, “Jackson State? C’mon, man, what you doin’ out here?” You had to prove something to them. Just because I’m at Jackson State doesn’t mean I’m a lesser baseball player. They got a chance to feel me.

You put Jackson State on the map for a bunch of ‘em, I’m sure.

Absolutely, man. The next year they got Earl Sanders out of Jackson State. Things started going on after that. So I like to call myself the Jackie Robinson of HBCUs for Cape Cod.

What a ride! And that was all before you played pro ball.

It was, man. When I got drafted, I went to short-season A ball in Bend, Oregon. It was 16-, 17-, 18-year olds. I’m 21. Every time someone wanted to get beer, they came to my house. I was the granddaddy up there. And I’m thinking I gotta get out. I was 9-5 and had a pretty good start to my pro career. Then the next year I was in Clearwater where the Phillies had all their top prospects at. My first three starts, I pitched three 3-hit complete game shutouts. They say I’m going up to Double A. I’m thinking I’m gonna be in the big leagues in about two months. I start feeling myself again.

I get to Reading in Double A. I think these guys are older, they’re gonna be a lot better, I gotta do a lot more. And I start pressing, and I start doing things contrary to what I did to get there, trying to throw every pitch as hard as I could. And Baseball America voted me to have the best fastball in the Eastern League. I had a 6.57 ERA and was 1-7. Ha! They sent me back to A ball. I was the first guy to get called up, the first guy to come back down.

I figured out what I was doing. It goes back to what I said. I needed a better approach. When they sent me back down to Clearwater, that’s what I worked on, being a better pitcher and not just trying to throw it. I’ve seen a lot of guys get released who throw 95 or 98 miles per hour because they don’t know how to pitch. Being able to learn the craft and teach it is what my mission has been, based on my experience as a player who went through that.

When I did figure it out, I started the next year in Double A. Got called up to the major leagues. The (second) game that I pitched was against the New York Mets, (September 21) 1986. Won that game. Pitched seven innings of one-hit ball and my daughter (Paris) was born in the fourth inning of that game.

Darryl Strawberry hit a triple off me in the (second) inning, and that was the only hit they got. He scored on a passed ball. They were leading 1-0. Glenn Wilson comes flying out of the clubhouse in the fourth inning saying, “Your wife just called. It’s a baby girl. Everything is fine and she says go out there and get the win.”

I start walking up and down the dugout saying I can’t get the win if I can’t get no runs. I think they put up a (four) spot. After the game, I’m at the airport and have my suit on. In one of those little gift shops, I went in and bought a briefcase, just so I could look the part when I got out of the cab and got to the hospital. It didn’t have nothing in it, totally empty. I’m carrying this thing and my wife is just coming out of recovery.

It’s still the greatest baseball day I’ve ever had in my life. First major league win and first child born on the same day. I bet that hasn’t happened a lot.

Do you still find time to get back to Jackson State?

Last time I went down there was about five years ago with my son. I’ve seen them at the tournaments they have in New Orleans, working with MLB. We do the Andre Dawson Classic. I work with a lot of HBCU kids with the Breakthrough Series and the Dream Series that MLB puts on. It’s a youth development program they have. I still have my hands on quite a few guys that play in the SWAC. I want to do a barnstorming coaches tour, just go through the SWAC and give these guys some pitching tips and instruction.

Every time I went down to Southern, I’d end up doing an impromptu training session in the parking lot with half the team. These guys would ask me for some advice, and I’d give it to them. They see what I do on my Instagram to give free training, free video analysis and free tips to kids all over the world.

Just being able to touch guys from all over and give them advice I learned and give them tips that I think could help them has been a real blessing for me and them.

So what ever happened to that rolltop desk you made in high school? Does somebody own that?

Yeah, it’s in my mother’s house! It’s a plant stand now. Every now and then, she’s gotta glue one of the drawers back together. The thing is 40 years old. But that’s the crown jewel, baby. That’s something we look back on. Every time I go see Mom, I tell the story. She’s like, “Yeah, yeah, yeah. You won second place.” She’s sick of hearing it. (laughing)

That’s a wonderful article about a great guy. Thank you Douglas Malan and Marvin Freeman.

Enjoyed the article on Roy Jackson. My team faced him. We played several years in the Tuskegee baseball tournament late seventies early eighties. They had a great team while Roy was there. They had a big first baseman named Phinessee. He was at least 250 lbs , but man could he ever hit.Roy was almost untouchable & helluable competitor. Glad to know he is well. Jackson State . email [email protected]

Also, Jackson State participated in the 1974 NCAA Regionals. They only lost four games in ’74. They lost two games to Tuskegee early in the season and went undefeated the rest of the way until dropping 2 in the NCAA Regionals. Playing right field during the second game of a doubleheader in the 1974 Jackson State V. Tuskegee game, I made a defensive play that snuffed out a Jackson State comeback in the fifth inning. With a Jackson State base runner on first base, I raced towards the right-field line on a grounder that got past Steve Duval, our first baseman—getting to the ball before it got into the corner, I made a throw to third base preventing the runner from advancing to third. So instead of runners on the corners or worst, a run scored and the batter ending up with a triple, JSU had runners at first and second with two outs. Our pitcher, former major leaguer Roy Lee Jackson, stuck out the next batter. JSU did not press us again; we left on a weekend road trip to Florida 5-5 on the young season. In the next game, we won a thriller to FAMU on the day Andre Dawson hit a homer off Skip Johnson that traveled at least 500 feet, landing on top of the gym over the palm trees in left. The next day, we dropped a one-run game to FAMU. Dawson was unstoppable. He went 8-8 in the two-game series.

Jackson had pitched the second game of the JSU doubleheader on a Wednesday and was unavailable in the FAMU series. So, I did not get to see these two future Major Leaguers square off against each other. Two days later, after a blessing out from Coach Jim Martin, we beat Bethune-Cookman 2-1. Roy Lee Jackson pitched a gem. The BCC pitcher was a tight left-hander who kept our bats quiet most of the game. In the seventh inning of this game, Bethune mounted a three with one out and a runner on first base. There batter hit a sweeping line drive to right field. I came in fast and had to make several adjustments as the wind took the ball and made it move like a knuckleball. Somehow I held on to make the catch and throwing behind the runner for the first time in my life. I almost doubled the runner off first. Jackson struck out the next batter, and we were back in the win column for the rest of the regular season. Tuskegee went on a 19 game winning rampage before losing a close match to LSU-New Orleans in the 1973 NCAA Southern Regionals.

When I was a kid growing up in the Northern suburbs of Chicago, along with my two brothers, we played “Strike Out” with a white rubber ball in the 1970s. Some of our baseball pick up games could not field a full squad so we either spray-painted or chalk the strike zone at the middle school side brick wall facing the field with the batter box drawn on the concrete surface. Those boxes were found everywhere.

In Strike Out, a pitch that was thrown inside the batter’s box was a strike. There was no bases to run so a hit was either judged as a single, double, triple or a home run depending on how far the ball was hit and traveled in the air. Outs were recorded as groundouts or a lazy fly ball.

The building was an important part of the game. It was a great way to play baseball without having a full 18 players. Usually a team had two to four players. It provide hours of fun to the game I fell in love with.

The is an excellent must read. The Marvin Freeman story send chills down my spine.

Marvin continues to give back, his heart and willingness to share his baseball expertise with underserved communities is unmatched. We are so fortunate that he moved to the metro Atlanta area. We appreciate you Big Fella.

Great info. I played on the 1972 and the 1973 tournament appearances.

Michael,

Jackson State was the first school to participate in an NCAA Division I regional tournament. Yes, you are correct about NCAA Division II. As a matter of fact, when my History of HBCU baseball book is finished and published (I need to call you), it will contain this excerpt…

Tuskegee University, in 1969, was the first HBCU baseball program to participate in an NCAA Division II post-season tournament, which was established the year before. The Golden Tigers appeared again in 1972 and then became the first HBCU to win an NCAA post-season tournament game by defeating Bellarmine College, 6-4 in the 1973 South Regional.

What an impressive piece of historical writing!!!

This article is an excellent piece about a superb human. I’ve been a fan of Freeman’s since his days as an Atlanta Brave reliever. A few years ago, while covering youth league baseball in the metro Atlanta area, I got to observe him gently barking out sage pitching wisdom to aspiring teenage pitchers.

For the record, Tuskegee University received bids to NCAA Regionals as far back as 1968. I know that the two teams that I played on at Tuskegee in 1972 and 1973 received NCAA Regional invitations. I believe the record shows Tuskegee as the first HBCU to win an NCAA regional baseball game. Stillman College had previously competed in the NAIA tournament and won some games. In a 1973 game, we beat, I think, Belmont College a lot to nothing. We played three games that day, winning one and losing two.

My college baseball career ended that day. Along with a dream I had held since age five of playing shortstop in Yankee Stadium. The Tuskegee NCAA Regional record stands at 1-6.

Great article!